- In this Special Report we consider how the dramatic expansion of the Fed's balance sheet has influenced the conduct of monetary policy from an operational perspective.

- Massive reserve balances have made the federal funds market largely irrelevant, but the Fed's new overnight reverse repo facility will allow it to tighten policy when the time comes.

- The Fed will likely provide new guidelines for its exit strategy before the end of 2014. We anticipate how these guidelines will be modified to reflect the challenges of implementing monetary policy with a large balance sheet.

- Large reserve balances do not pose an inflation threat, but they do have implications for the state of banking sector regulation and the policy tools at the Fed's disposal.

Chart 1

What Are Implications Of Fed's Epic Intervention?

Fullscreen Fullscreen |  Interactive Chart Interactive Chart |

Feature

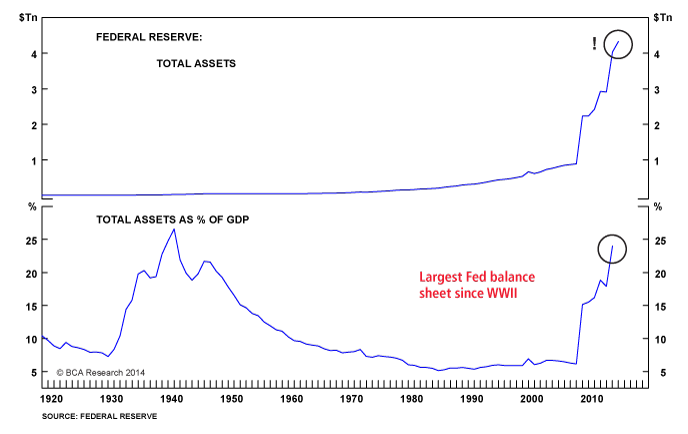

The Federal Reserve resorted to a number of very aggressive and extraordinary monetary policy measures to deal with the failure of Lehman Brothers, the subsequent financial crisis and Great Recession. The result has been a flood of liquidity that has supported asset prices and spurred the recovery, yet has left the central bank balance sheet exponentially larger than at any time in its 100-year history (Chart 1).

In formulating its exit strategy the Fed will finally be forced to grapple publicly with the aftereffects of its dramatic intervention in financial markets, which has complicated how monetary policy is implemented at an operational level.

This Special Report is divided into three sections. In the first section, Before The Storm, we provide some background on the process of money creation and explain how the Fed implemented monetary policy prior to the Great Recession. In the second section, The Flood Waters Rise, we consider how monetary policy is implemented today in light of the dramatic expansion of the Fed's balance sheet. In the third section, Building On Higher Ground, we examine the way forward for the Fed, describe how the exit is likely to be managed and discuss the potential problems with this approach.

1. Before The Storm

Prior to the financial crisis, the Fed expressed the stance of monetary policy via a target for the federal funds rate. The federal funds rate is the rate at which banks borrow and lend reserves to each other in the overnight market. The Fed conducted its day-to-day operations with the goal of supplying all the reserves demanded by the banking sector, while steering the fed funds rate toward its target. To understand how this was accomplished, we first require some background on the money creation process.

Money Creation: More Than Just A Printing Press

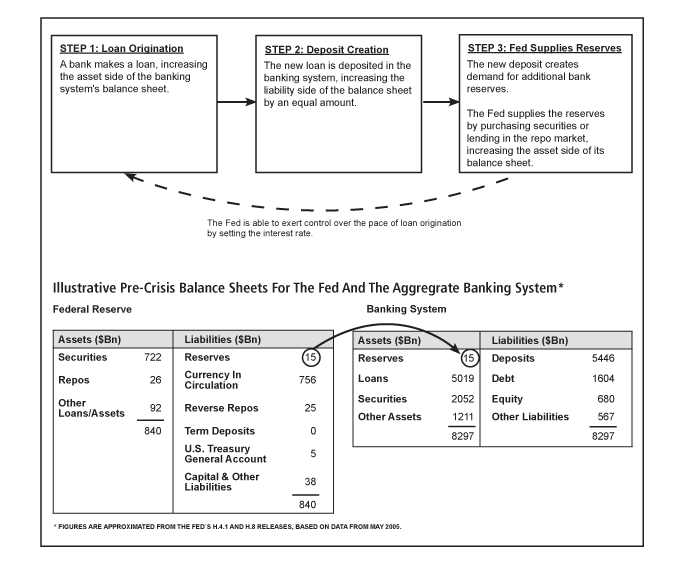

Contrary to what many believe, the process of money creation does not begin at the Federal Reserve. Rather, it begins in the banking system at the point of loan origination and ends at the Fed (Figure 1). The process is set in motion when a bank makes a new loan. This loan creates a new asset on the aggregate balance sheet for the banking system. The newly created money typically ends up as a deposit, either at the same bank or elsewhere in the banking system.1 The increase to the asset side of the banking sector's balance sheet is offset by an equal increase on the liability side.

Only then does the Fed enter the picture. In a fractional reserve system, banks must hold reserves equal to a proportion of their deposits. Therefore, in the pre-QE world illustrated in Figure 1, any increase in deposits also creates demand for more reserves. Crucially, only the Fed is able to supply the banking sector with the needed reserves. The Fed will increase the supply of reserves either by purchasing Treasury securities or lending money in the repo market. This increase on the asset side of the Fed's balance sheet is balanced by an increase in reserves on the liability side. The creation of new bank reserves is the final step in the money creation process.

Figure 1

The Money Creation Process

Fullscreen Fullscreen |

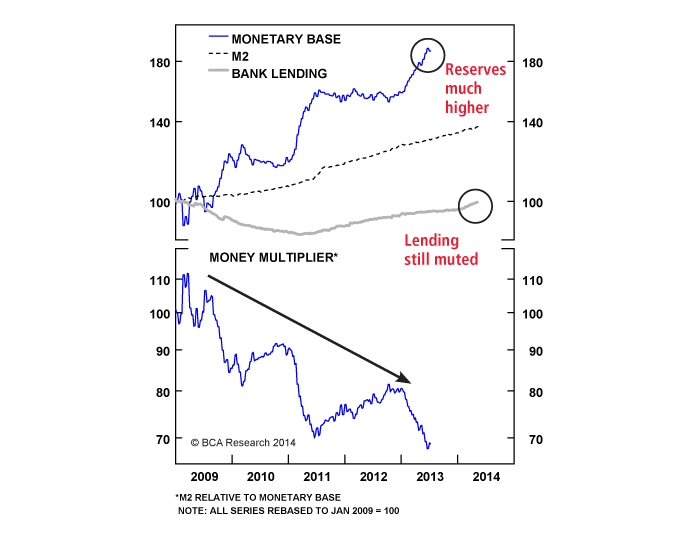

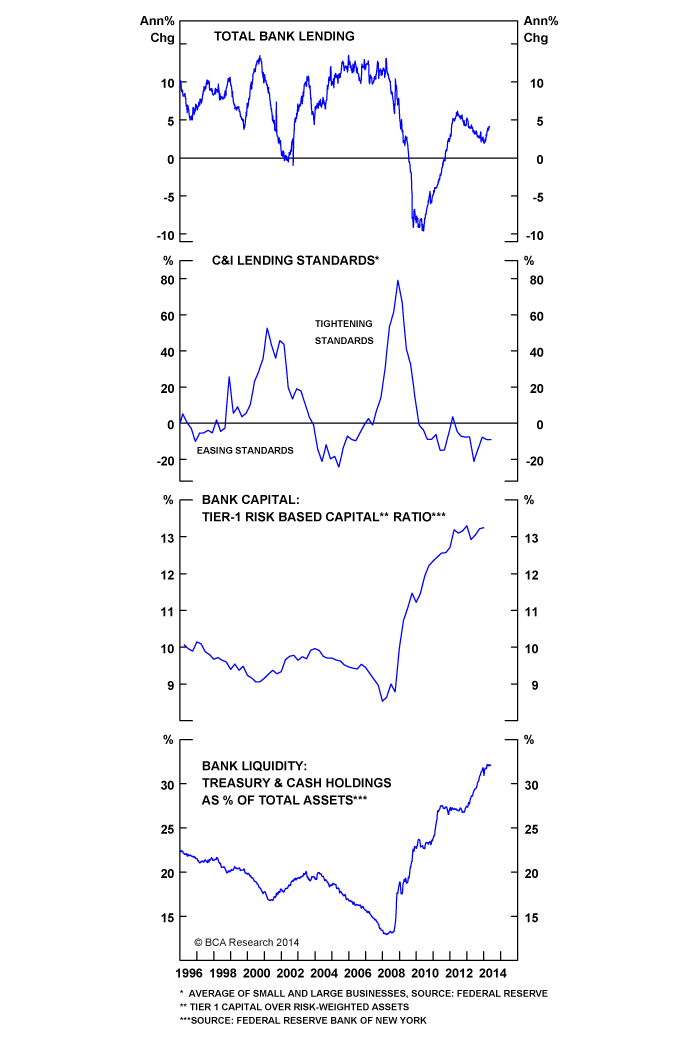

This is not to suggest the Fed is powerless to control the rate of money creation. On the contrary, Fed policy is the most influential determinant of the rate of money growth. One important distinction, however, is that the Fed exerts control over the pace of money creation because it controls the overnight interest rate. The interest rate, in turn, is the most important driver of bank lending. Changes in the level of bank reserves not associated with changes in interest rates, QE for example, have no effect on credit growth (Chart 2).

Chart 2

QE Has Not Encouraged Lending

Fullscreen Fullscreen |  Interactive Chart Interactive Chart |

The Pre-Crisis Fed Funds Market

How then, prior to the Great Recession, was the Fed able to maintain the fed funds rate at its target, while still satisfying the banking system's demand for reserves? It accomplished this task by maintaining what it calls a "structural deficiency" in the supply of bank reserves. In practice this means the Fed was careful to supply no more than the quantity of reserves demanded, so that each day it would typically add to the reserve supply to accommodate the newly created demand.

As a practical matter, the Fed increases the supply of reserves by either buying securities or lending money in the repo market. Both of these transactions enter the Fed's balance sheet as an asset, which must be offset by a liability, in this case an increase in bank reserves. The Fed can also reduce the supply of reserves by either selling securities or borrowing in the repo market (using the securities it owns as collateral, deemed a reverse repo from the point of view of the borrower). Although due to the "structural deficiency" in the reserve market, the Fed would typically transact to increase reserve balances.

If, for example, the Fed wanted to increase the fed funds rate. It would be slow to accommodate the increase in demanded reserves throughout the day. Banks in need of reserves to meet intra-day payment processing needs would bid up the fed funds rate towards the new target. Effective communication of the target fed funds rate also aided this process. Since the target for the fed funds rate was known in advance, and the banking sector believed the Fed would supply all necessary reserves at that target rate, most federal funds transactions tended to occur at rates very close to the target.

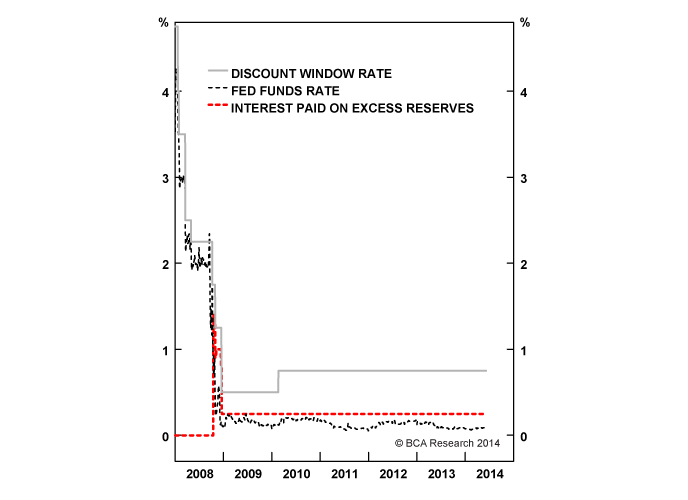

By the end of the day, however, the Fed must always supply the exact amount of reserves demanded by the banking sector if it wants to maintain control of the fed funds rate. If the Fed were to supply more reserves than the banking system required, banks would try to lend the unwanted excess reserves in the fed funds market, driving the federal funds rate lower to the interest rate paid on excess reserves (IOER), which was zero prior to 2008. Or, consider the opposite case where the Fed supplies too few reserves. In this instance banks would clamor to borrow reserves to meet their regulatory requirement. This incremental demand would drive the federal funds rate higher to the Fed's discount window lending rate, which is always available for banks to access in times of severe stress.

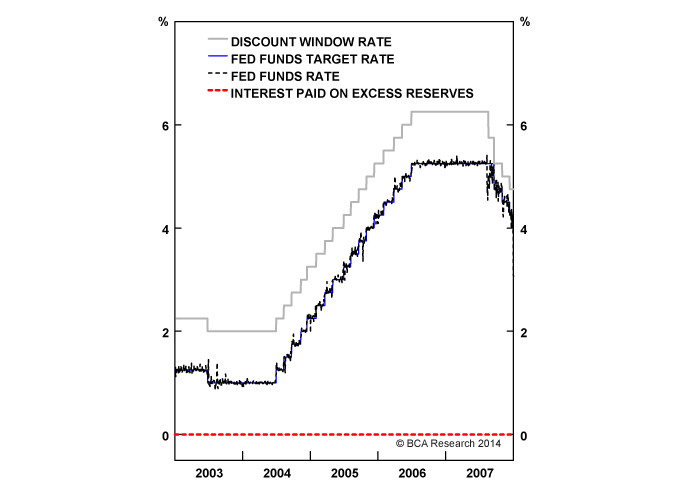

The IOER and discount window rate thus created a channel for the fed funds rate (Chart 3), within which the Fed could nudge the rate toward target by being either too quick, or too slow to accommodate increases in demanded reserves throughout the day.

Chart 3

The Pre-Crisis 'Channel System'

Fullscreen Fullscreen |  Interactive Chart Interactive Chart |

2. The Flood Waters Rise

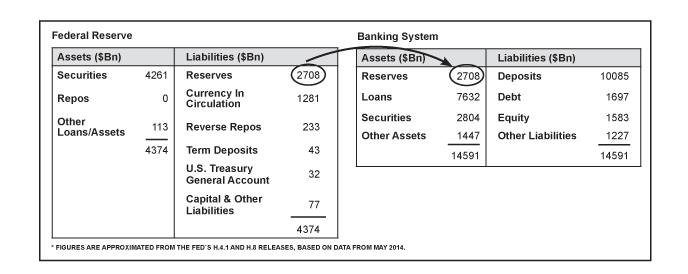

The Federal Reserve began large scale asset purchases (quantitative easing) in late 2008, dramatically increasing the asset side of its balance sheet and consequently the supply of bank reserves (Figure 2). Suddenly, the banking system found itself with far more reserves than it demanded. Predictably, trading in the fed funds market dried up and the fed funds rate was driven toward its lower bound, the IOER.2 The Fed's target for the federal funds rate quickly became irrelevant.

Figure 2

Illustrative Post-Crisis Balance Sheets For The Fed And The Aggregatve Banking System*: An Explosion In Excess Reserves

Fullscreen Fullscreen |

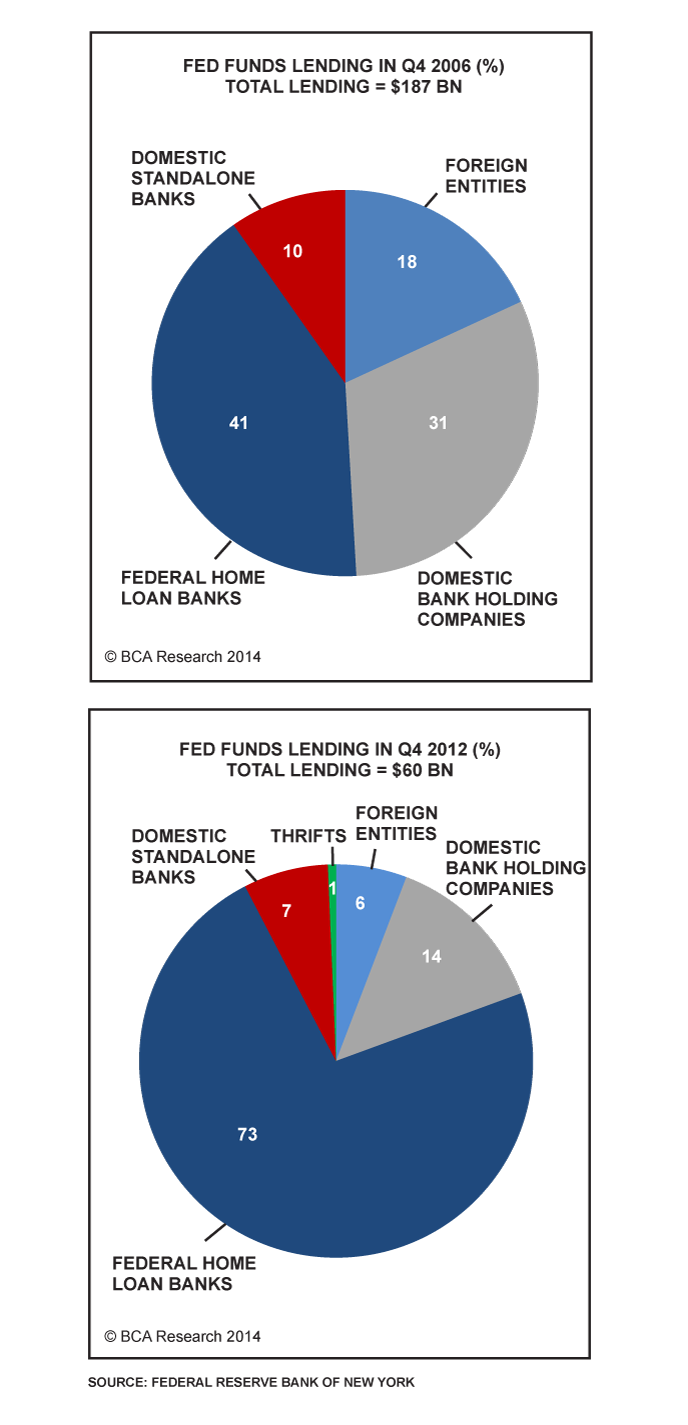

In the presence of excess bank reserves, the Fed needs a mechanism to control the lower bound of overnight lending rates. In theory, the IOER could serve as a floor beneath the fed funds rate because banks should not be willing to lend reserves at a rate lower than what can be earned at the Fed. Yet the fed funds rate has consistently traded below the IOER since 2008 (Chart 4). The reason for this violation is that the IOER is only available to depository institutions with reserve accounts at the Fed. Other suppliers of short maturity funds, mostly the GSEs, are still willing to transact at lower rates (Chart 5).

Fullscreen Fullscreen |  Interactive Chart Interactive Chart |

Chart 5

Fed Funds Market Smaller, And Dominated By GSEs

Fullscreen Fullscreen |

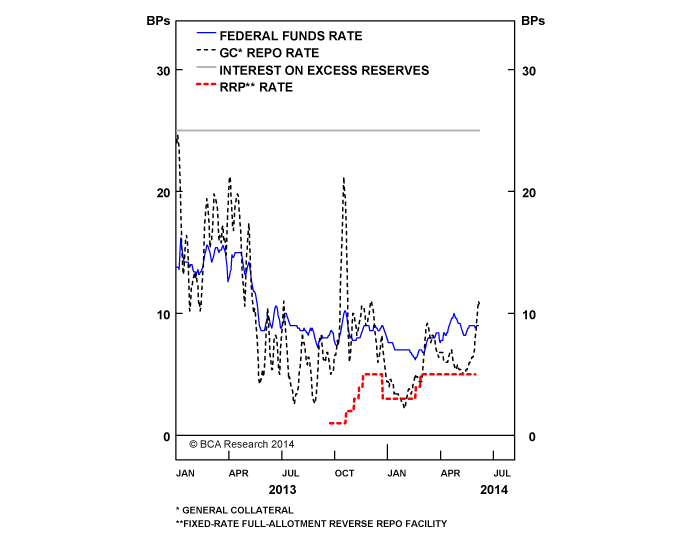

A new facility is required, that is capable of absorbing all of the supply of overnight funds including that emanating from outside the traditional banking system. The Fed answered this requirement by creating a fixed rate overnight reverse repo (RRP) facility. Once fully implemented, the Fed will stand ready to borrow overnight in unlimited amounts, at a rate that it chooses (i.e. is set independently of market forces). By making this facility available to a larger set of counterparties than the IOER, including money market funds and the GSEs, the Fed now has a "hard floor" on rates that it will be able to use to raise interest rates when the time comes. Even though it is still in a testing phase, the RRP already appears to be acting as a floor for overnight rates (Chart 6).

Chart 6

Reverse Repo Facility Is New Floor On Rates Money Markets Under The Microscope

Fullscreen Fullscreen |  Interactive Chart Interactive Chart |

3. Building On Higher Ground

From an operational perspective, there are two possible ways forward for the Fed as it prepares to lift rates. One option would be to return to the pre-crisis method of operation described in the first section. To do this, the Fed would first have to drain all excess reserves from the banking system by either selling securities, or deploying some of the tools on the liability side of its balance sheet, such as term deposits.3 This would re-launch the federal funds market and the Fed could return to setting policy in its traditional manner, by targeting the fed funds rate. Unfortunately, there are simply too many excess reserves in the system to make this a viable strategy, at least for the next several years. Moreover, the pace of asset sales required to drain excess reserves in a timely manner would lead to large spikes in the Treasury term premium.

Instead, the Fed will almost certainly choose to maintain large reserve balances and operate monetary policy by lifting the floor RRP rate. Specifically, the Fed will set the RRP rate equal to (or slightly below) the IOER. It will then hike rates by increasing both in tandem. The Fed may still choose to set a target for the fed funds rate at a level somewhat above the RRP to maintain consistency in its communications, but this rate will be meaningless. We outline the likely sequence of the Fed's exit strategy in the following Box.

The Exit Strategy RevisitedThe Fed first articulated the likely sequence of the exit strategy in the minutes to the June 2011 FOMC meeting.4 That sequence was as follows:

- Cease reinvestment of principal on securities holdings.

- Modify forward guidance on the path of the federal funds rate, and initiate reserve draining operations (e.g. term deposits).

- Begin raising the target federal funds rate.

- Begin sales of securities holdings, with a goal of returning the balance sheet to a more traditional size within two to three years.

- Modify forward guidance on the path of interest rates (including IOER, RRP and fed funds).

- Begin raising interest rates. First by raising the RRP rate to slightly below the IOER, and then by raising both rates in tandem.

- A few months after rate hikes begin; cease reinvestment of principal on Agency and Agency MBS holdings.

- Much later; cease reinvestment of principal on Treasury securities.

In the next few years, as its balance sheet begins to shrink through passive run-off, the Fed may decide to drain the remaining excess reserves and return to its traditional operating method as outlined in Section1 above. Either way, U.S. monetary policy will operate under a "floor system", using the RRP rate, for at least the next few years. This new method of operation comes with several potential drawbacks, which we address below.

Excess Reserves Are "Dry Powder" For The Banking System

Many have speculated that banks have been choosing to sit on large excess reserve balances. The thinking is that eventually the economy will reach a turning point and banks will decide to convert their excess reserves to loans en masse, leading to a surge in bank lending, and eventually, inflation. This implies that the presence of large excess reserve balances would force the Fed to hike rates more quickly than in their absence. This concern stems from a misunderstanding of the money creation process described above. The Fed could fall "behind the curve" and normalize policy too slowly, which could ultimately lead to higher inflation. However, this would simply be a consequence of keeping interest rates too low for too long. The presence of excess reserves does not in itself create a desire to lend and thus poses no additional inflation risk.

For one thing, the banking system in aggregate is powerless to reduce the amount of excess reserves without the Fed also taking action to reduce the supply. As shown in Figures 1 and 2, the supply of excess reserves is determined solely on the Fed's balance sheet. There is no danger of excess reserves "leaking out" into the economy.

More importantly, however, is that the process of money creation begins with the origination of a loan and ends when the Fed increases the supply of reserves. The catalyst for the process, the amount of bank lending, is determined by (Chart 7):

Chart 7

Drivers Of Bank Lending

Fullscreen Fullscreen |  Interactive Chart Interactive Chart |

- loan demand

- banks' perceived profitability from additional lending

- banks' concerns about taking too much risk on the balance sheet, putting their viability at risk

- regulatory requirements concerning capital and liquidity

The Fed exerts control over these four factors through its interest rate policy, but not through changes in the balance of excess reserves. Prior to 2008, the lack of excess reserves did not act to constrain bank lending, rather the Fed chose to encourage or discourage lending by decreasing or increasing the interest rate. Similarly, the large excess reserve balances since 2008 have not provided an incentive to lend.

Excess Reserves and Bank Regulation

One implication of the Fed having sole control over the supply of bank reserves is that, through QE, it has effectively forced reserves onto bank balance sheets. These reserves obviously factor into banks' calculations concerning required regulatory ratios for liquidity and capital.

Liquidity Coverage Ratio

Under the proposed liquidity coverage ratio (LCR), banks must maintain a balance of high-quality liquid assets (such as bank reserves and Treasury securities) equal to their expected net cash requirement during a 30-day period. In theory, should the Fed ever decide to reduce the supply of excess reserves, banks could have trouble meeting the LCR requirement. In removing reserves, however, the Fed would also be selling securities. Banks falling short of their LCR requirement would be natural buyers for the securities offloaded by the Fed. Thus, the Fed's operating decisions will probably not exert any influence over banks' ability to meet their liquidity requirements.

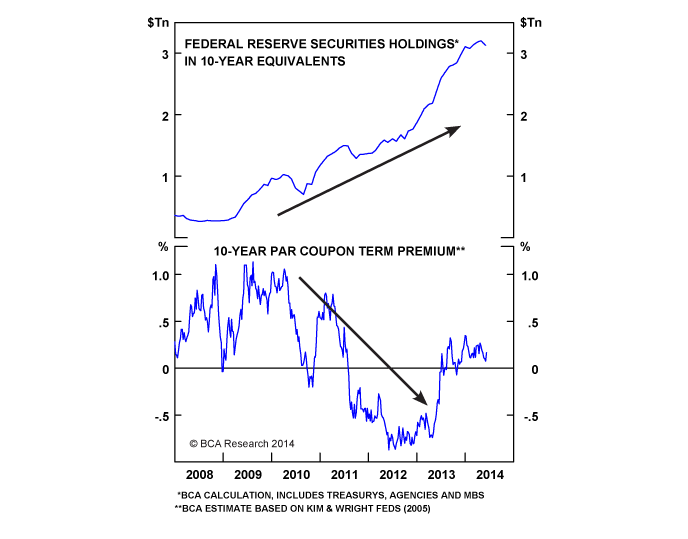

The LCR, however, does have implications for the equilibrium level of the Treasury term premium. Much as the Fed's Treasury purchases pressured the term premium lower (Chart 8), any future Treasury sales could be expected to unwind this effect. Even so, bank demand for those same Treasury securities would mitigate some of the upside for the term premium.

Chart 8

Fed Purchases Pushed Term Premium Lower

Fullscreen Fullscreen |  Interactive Chart Interactive Chart |

Supplementary Leverage Ratio

Large U.S. banks face a supplementary leverage ratio (SLR) which requires them to hold capital equal to at least 5% of total assets, not risk-weighted. In other words, large excess reserves force banks to hold more capital, which could have an adverse economic impact.

Banks falling short of the SLR can either raise capital, or reduce assets. If they are either unable or unwilling to raise capital, then the large balance of excess reserves thrust upon them by the Fed could in theory crowd out bank lending. In other words, if the banking sector refuses to increase capital, then the onus falls on the asset side of the balance sheet to adjust to SLR standards. Since the banking sector in aggregate is unable to reduce reserve balances, any desired contraction in total assets could conceivably translate into an incentive to reduce the pace of bank lending.

As currently proposed the SLR does not appear to be too big a hurdle for the largest U.S. banks. It is very likely they will be able to meet the requirement through retained earnings and new equity issuance. Nevertheless, it still provides a potential drag on bank lending that would not exist under the traditional model of monetary policy operations.

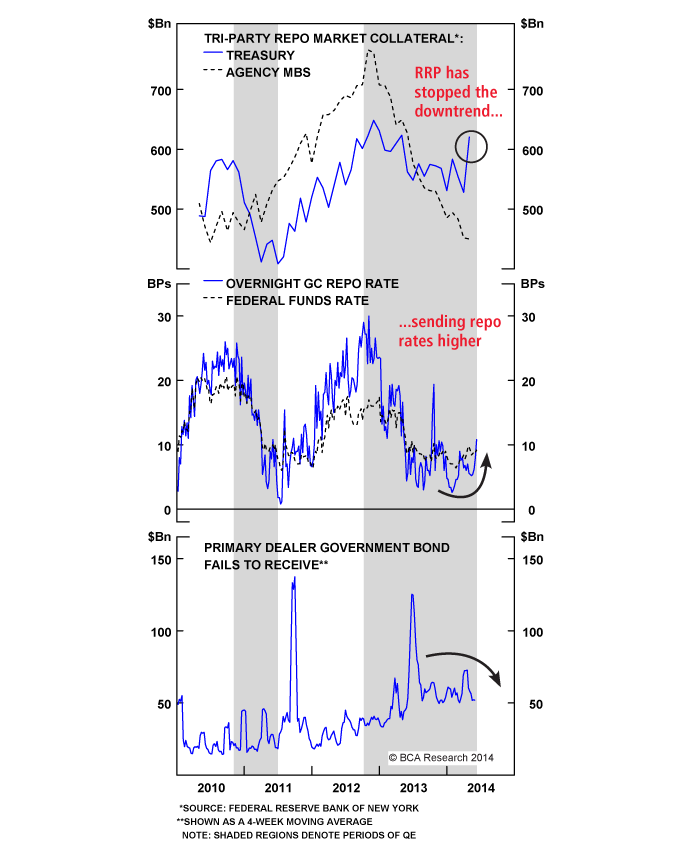

Collateral Shortage

One side effect of the Fed's large scale asset purchases is that they have removed a lot of high-quality collateral from the financial system. Chart 9 shows that during periods when the Fed is adding to its balance sheet, the amount of collateral in the tri-party repo market declines. As the supply of collateral dwindles, repo rates are also pressured lower. The problem is that once repo rates approach the zero lower bound, counterparties have an increasing incentive to fail on delivery of repo contracts. Given the widespread use of repo financing, persistent repo fails have the potential to undermine liquidity in financial markets. Thankfully, the Fed's new tool for controlling the overnight interest rate, the RRP facility, solves this problem.

Chart 9

RRP Alleviates Collateral Shortage

Fullscreen Fullscreen |  Interactive Chart Interactive Chart |

In a reverse repo transaction, a counterparty purchases securities from the Fed with the understanding that it will sell them back the next day, earning the RRP rate in the process. This means the private sector once again gains access to collateral that had been cordoned off on the Fed's balance sheet. This should have the effect of keeping the repo rate above the floor set by the RRP, and well above zero. Repo fails have already levelled off and should begin to decline once the RRP facility is fully implemented.

Financial Stability Concerns

We have seen that monetary policy operates under a floor system when there are large reserve balances. One complication is that the U.S. is operating with two different floors, the IOER and the RRP. Due to its availability to a wider selection of counterparties, the RRP is the true floor on rates. From a monetary policy perspective, the easiest way forward is to set both rates at the same level and hike them in tandem. However, in a recent speech5New York Fed President Dudley pointed out that from a financial stability perspective an RRP rate equal to the IOER could result in money flowing out of institutions eligible to receive IOER and into the less regulated shadow banking sector. It is therefore probable the Fed will choose to maintain the RRP at a level slightly below the IOER as rate hikes commence. We maintain focus on the RRP as the true floor on rates.

President Dudley also made the case that the Fed's RRP facility could have positive implications for financial stability. He observed that with a Fed-backed short-term safe asset now more widely available, it could crowd out the creation of money-like liquid assets by the private sector. Those privately created liquid assets, such as commercial paper, are more prone to fire sales during times of stress. In a recent paper,6 John Cochrane agreed forcefully with this sentiment. Due to its potential for eliminating privately created money-like liquid assets, Cochrane referred to a monetary policy regime operating with large reserve balances as "a very desirable configuration of monetary affairs."

The downside of the Fed providing a short-term safe asset is that it could encourage runs into the RRP during times of crisis. President Dudley rightly concludes that this is more of a technical hurdle that could be managed using caps on usage of the RRP facility.

- 1 Alternatively it could be held in cash. This would be reflected on the banking sector's balance sheet as an increase in loans and a decrease in reserves, and on the Fed's balance sheet as an increase in currency in circulation and a decrease in reserves.

- 2 The Fed began paying interest on excess reserve balances on October 6, 2008.

- 3 The Fed's current Term Deposit Facility (TDF) temporarily drains reserves from the banking system by receiving funds from the banking sector for a period of 7 days, paying 26 basis points of interest. The early stages of the Fed exit strategy will rely more heavily on the overnight RRP facility rather than the TDF. But term deposits could be deployed once the Fed's balance sheet has returned closer to its traditional size, and the Fed decides it wants to drain the remaining excess reserves and return to its pre-crisis method of operation.

- 4 http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcminutes20110622.pdf

- 5 "The Economic Outlook and Implications for Monetary Policy" available at http://www.newyorkfed.org/newsevents/speeches/2014/dud140520.html

- 6 Cochrane, John H. Monetary Policy with Interest on Reserves. Available at http://media.hoover.org/sites/default/files/documents/2014CochraneMonetaryPolicywithInterestonReserves.pdf

You are reading a complimentary report. To find out more about our services,

You are reading a complimentary report. To find out more about our services,