Feature

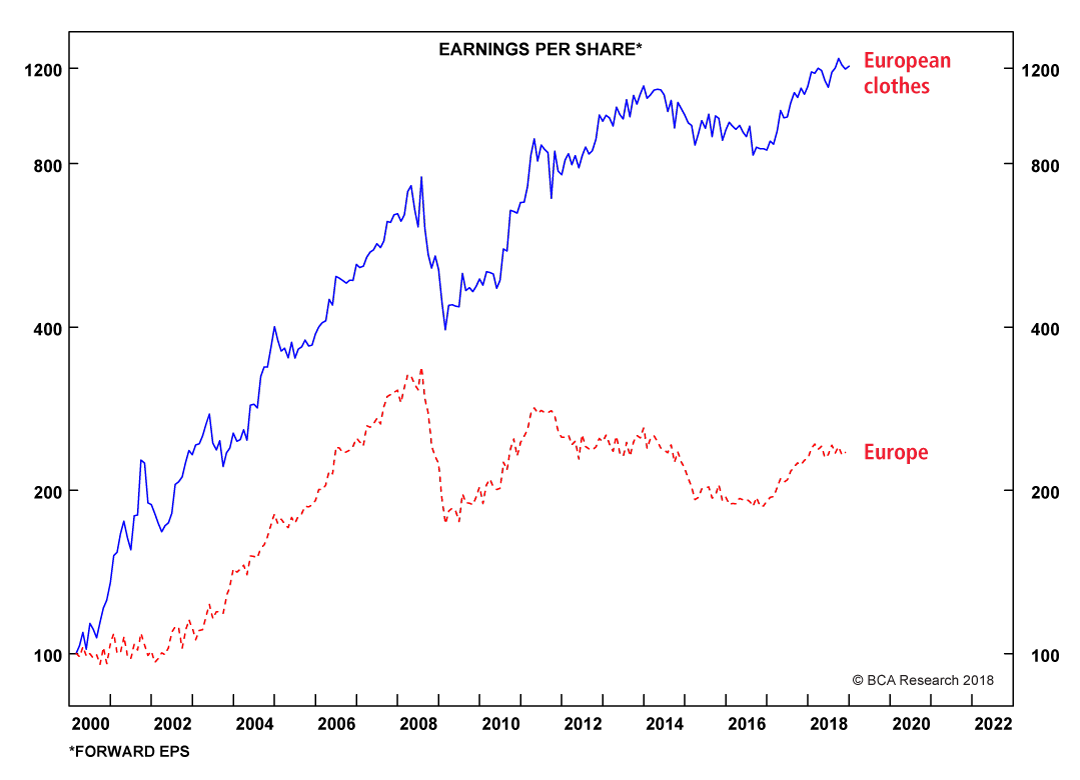

The European stock market has a hidden gem: its clothing and accessories sector. Since the turn of the millennium, the sector’s profits are up by a thousand percent (Feature Chart). In this Special Report we propose that the megatrend has further to run, as its principle driver is still very much in place. Consumption patterns are becoming more female.

Feature Chart

European Clothes Profits Are Up A Thousand Percent!

Fullscreen Fullscreen |  Interactive Chart Interactive Chart |

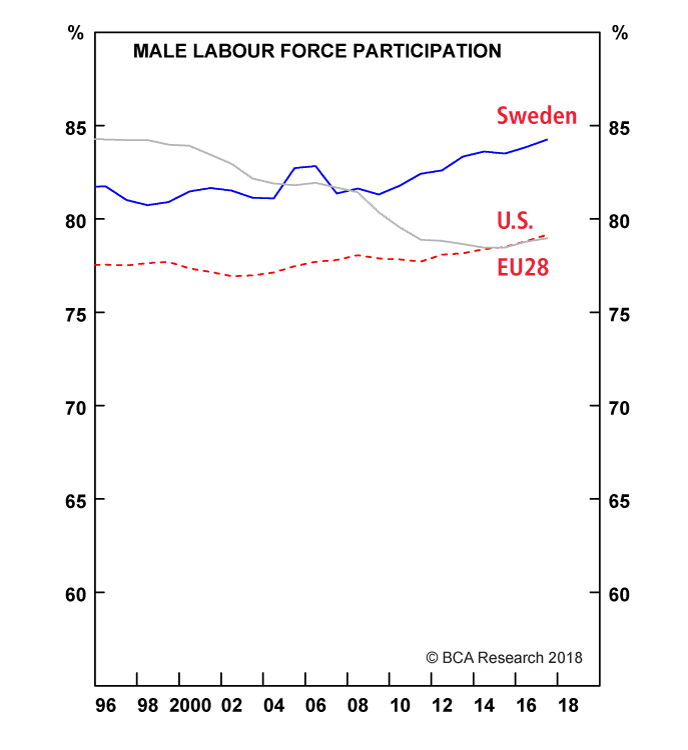

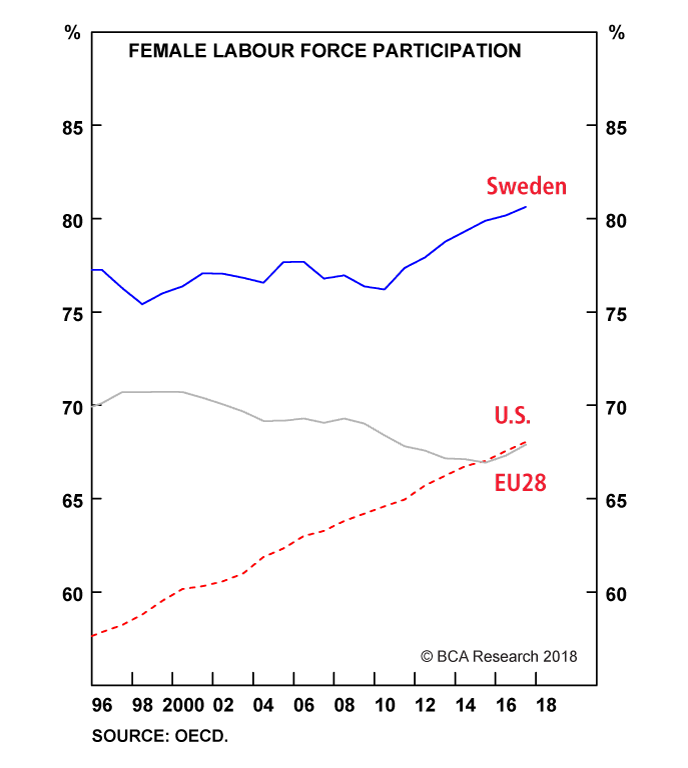

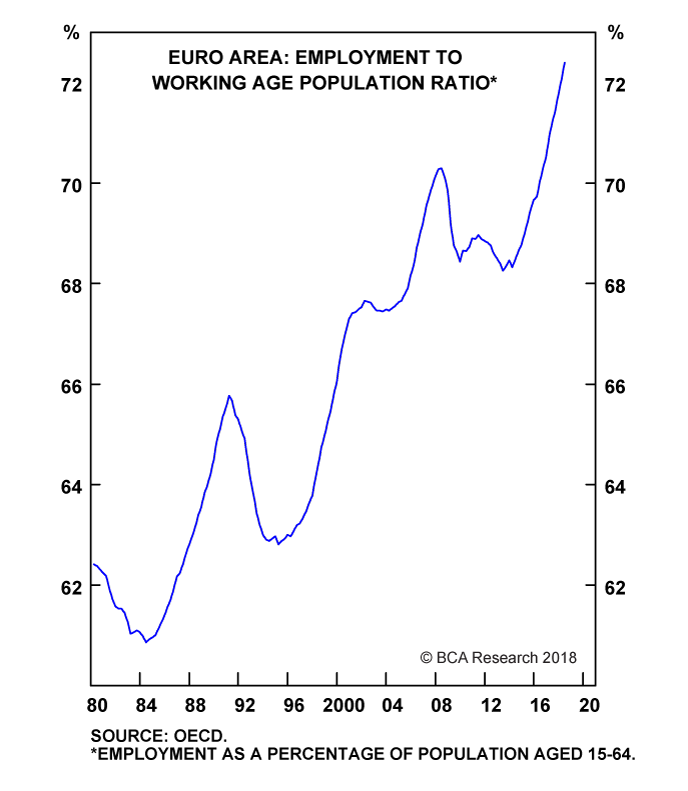

One of Europe’s major, and largely neglected, success stories is the dramatic rise in the percentage of the working-age population in employment. This major success story stems from another success story: the structural and broad-based increase in the female labour participation rate – which has surged from 57 percent in 1995 to 68 percent today (Chart I-2-Chart I-4). Yet the story is far from over.1

Chart I-2

European Male Labour Participation Is Flat...

Fullscreen Fullscreen |  Interactive Chart Interactive Chart |

Chart I-3

...But European Female Labour Participation Is Surging

Fullscreen Fullscreen |  Interactive Chart Interactive Chart |

Chart I-4

...So The Percentage Of The European Population In Work Is Surging

Fullscreen Fullscreen |  Interactive Chart Interactive Chart |

Why Job Creation Favours Women

Two things are driving the megatrend in female participation. One is a paradoxical feature of the current technological revolution. As we explained in The Superstar Economy: Part 2, Artificial Intelligence (AI) excels at tasks that we perceive as difficult: those requiring the application of complex algorithms and pattern recognition to a narrowly defined goal, such as making a highly-engineered product or managing a stock portfolio. This poses a big threat to jobs in manufacturing and finance, employment sectors which happen to be male-dominated.2

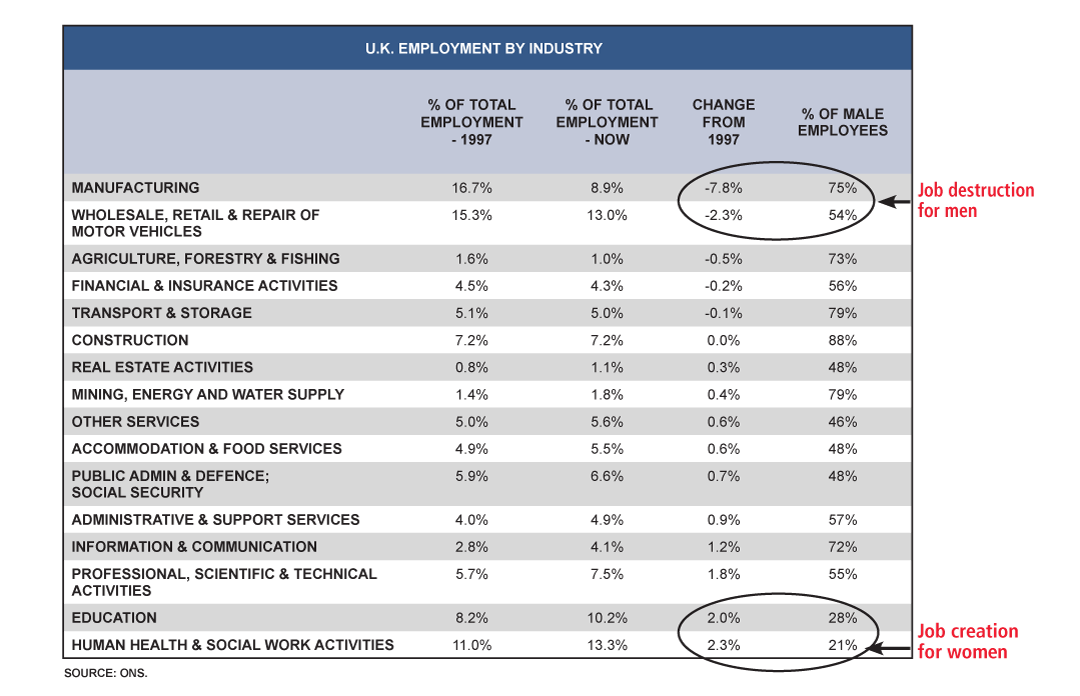

Conversely, AI still struggles at tasks that we perceive as easy: those requiring adaptable movements, or reading and responding to people’s emotions and intentions. If you are good at controlling a disruptive class of 7-year olds, or calming a nervous patient before giving him an injection, your human skills are still in big demand. But education, healthcare, and social care – the employment sectors that are creating the most jobs – employ three times as many women as men. With AI still in its infancy, the established pattern of job destruction and creation will continue to favour women over men (Table I-1).

Table I-1

AI Is A Greater Threat To Men

Fullscreen Fullscreen |

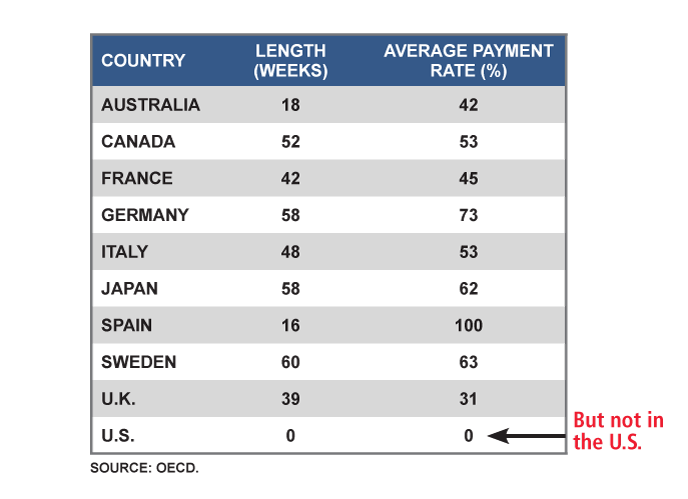

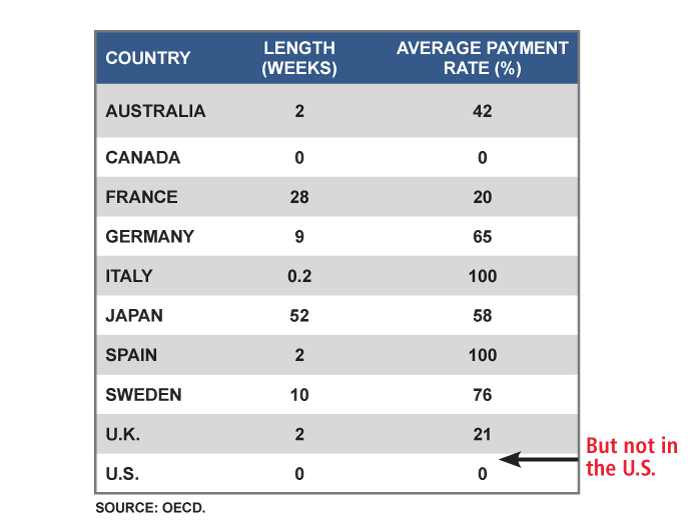

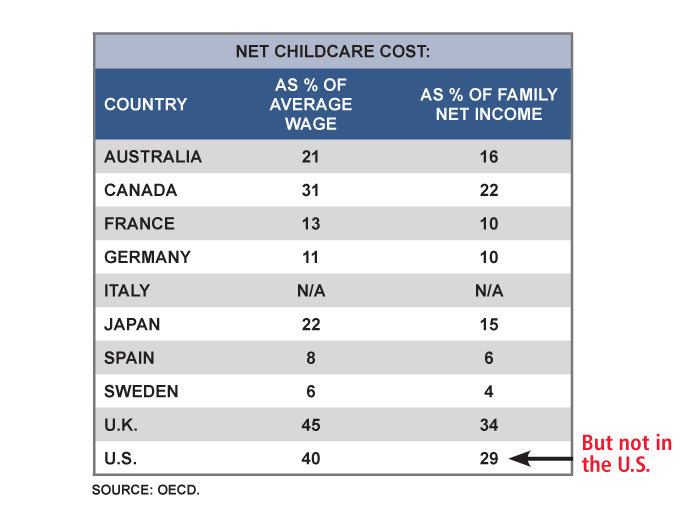

The other driver of the megatrend in female participation is a raft of European legislation designed to make work more family friendly: flexible working time, generous paid maternity and paternity leave, and subsidised childcare (Table I-2-Table I-4). Sharing the responsibility of childcare between mothers, fathers and external helpers has allowed tens of millions of European women to enter and remain in the labour force.

Table I-2

Generous Maternity Pay In Europe And Japan

Fullscreen Fullscreen |

Table I-3

Improving Paternity Pay In Europe And Japan

Fullscreen Fullscreen |

Table I-4

Affordable Childcare In Europe And Japan

Fullscreen Fullscreen |

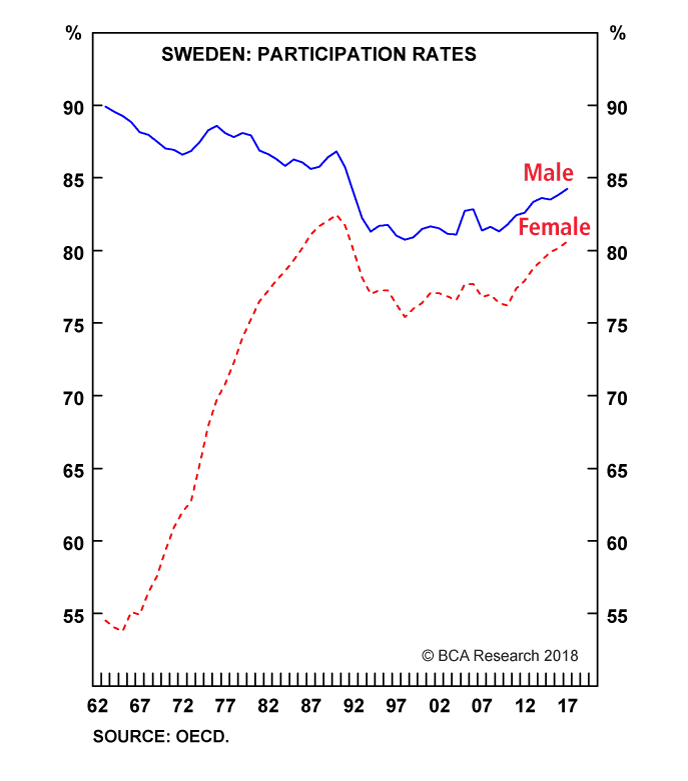

Nevertheless, the megatrend has a lot further to run. For the ultimate end-point, look at the Scandinavian countries which started legislating such policies in the early 1970s, around twenty years before the rest of Europe. As a result, in Sweden, labour force participation rates for women and men have now converged to almost identical: 81 versus 84 percent (Chart I-5).

Chart I-5

In Sweden, Labour Force Participation For Women And Men Is Almost Identical

Fullscreen Fullscreen |  Interactive Chart Interactive Chart |

The combination of the two drivers – employment growth favouring female-dominated sectors and employment becoming more family friendly – means that net job creation in Europe will be mostly due to more women joining the workforce. An important consequence is that consumption patterns will continue to become more female. But what does that mean?

How Women’s Spending Differs From Men’s Spending

In the main spending categories of housing, food and healthcare, women and men tend to show near-identical spending behaviours. But there are three sub-categories where there are significant differences.

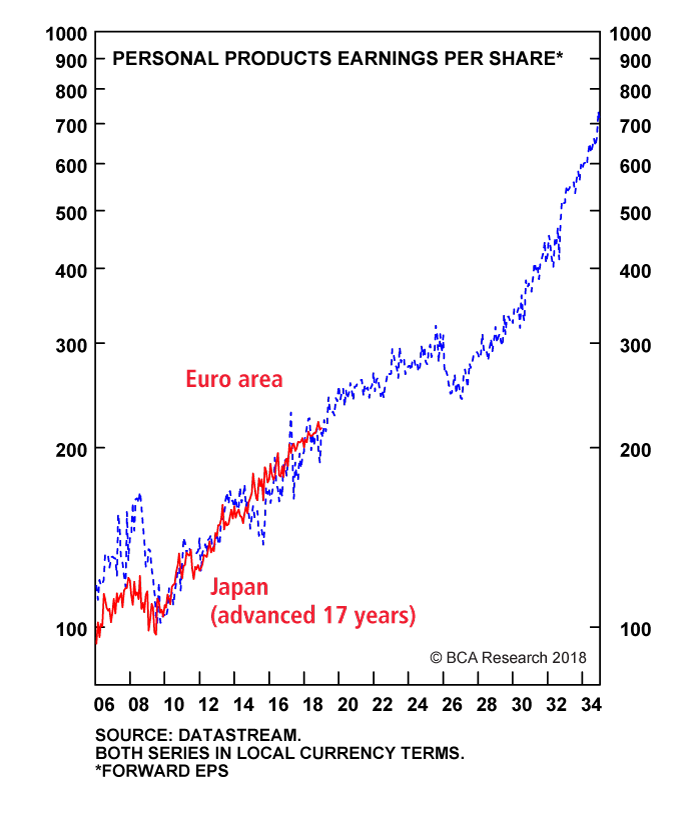

Men considerably outspend women on vehicle purchases: cars account for around 8 percent of disposable income for men versus 4 percent for women. Against this, women spend more on personal care products and services: 2 percent versus 0.5 percent. This is the reason behind our long-standing successful overweight recommendation in the European personal products sector which we maintain (Chart I-6). However, the sub-category in which women outspend men by even more is clothes and accessories: estimates average around 6.5 percent for women versus 2.5 percent for men.3

Chart I-6

Personal Product Profits Set To Grow Very Strongly

Fullscreen Fullscreen |  Interactive Chart Interactive Chart |

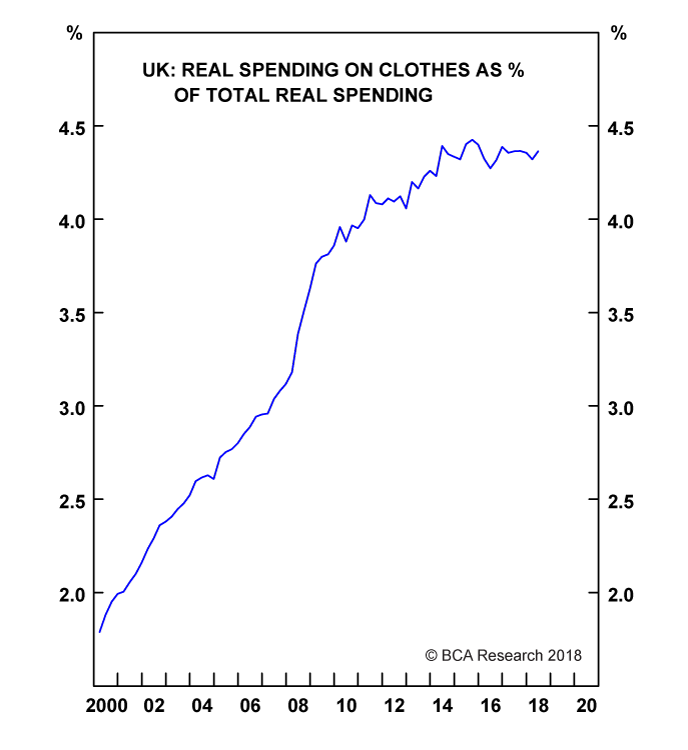

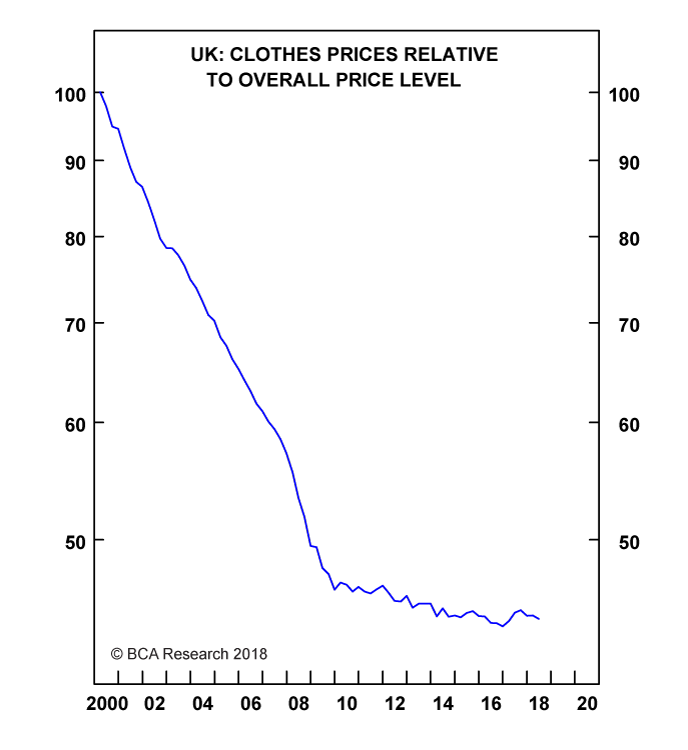

It follows that as consumption patterns become more female, we should expect to see a steady rise in spending on clothes and accessories as a share of total consumer spending. Has this been the case? In the U.K. – where the data is easily available – the answer is yes (Chart I-7). Having said that, other factors are also at play. A generalised deflation in clothes prices (Chart I-8) is also generating a strong tailwind to sales volumes (rather than values). More about this later.

Chart I-7

More Real Spending On Clothes...

Fullscreen Fullscreen |  Interactive Chart Interactive Chart |

Chart I-8

Partly Because Clothes Prices Are Falling...

Fullscreen Fullscreen |  Interactive Chart Interactive Chart |

Of course, the more compelling evidence is the thousand percent growth in the European clothes sector’s profits since the turn of the millennium. However, with the sector dominated by top brands such as LVMH and Hermes, could a more plausible explanation come from strong economic growth, until recently, in the emerging markets such as China?

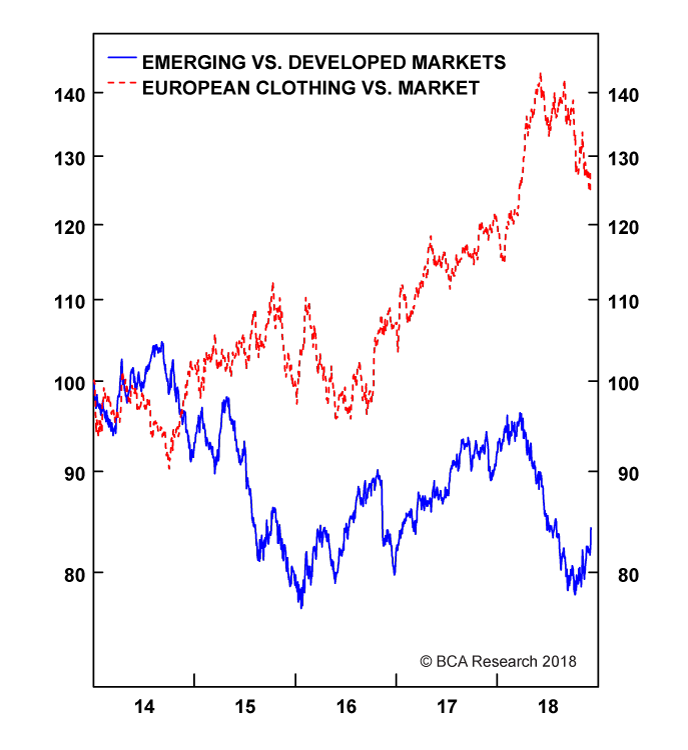

The answer is yes to the extent that many of the emerging economies are experiencing the same structural uptrends in female participation, and this supports our investment thesis. Still, this cannot be the main driver, because in recent years the connection between the fortunes of the emerging economies and the European clothes sector has been weak (Chart I-9).

Chart I-9

The Connection Between Emerging Markets And European Clothes Is Weak

Fullscreen Fullscreen |  Interactive Chart Interactive Chart |

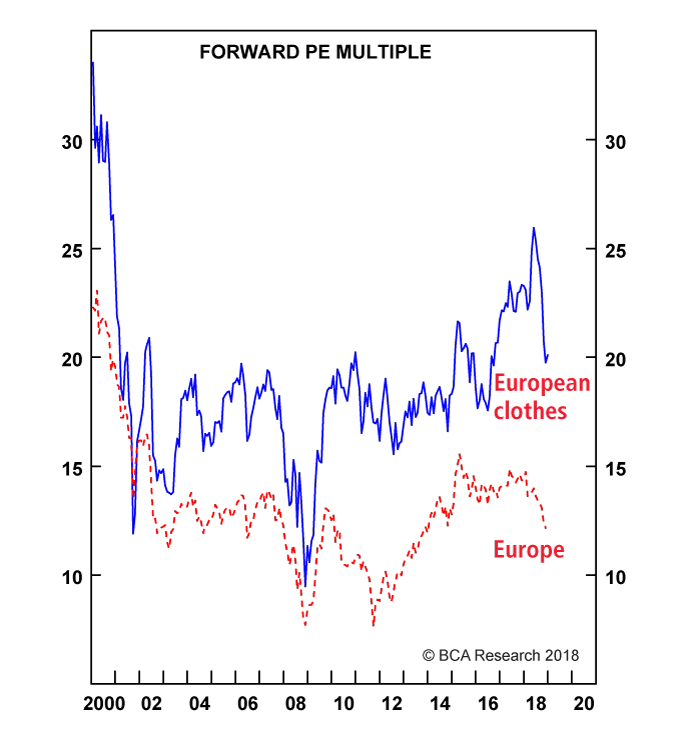

There is another obvious question: is the market already aware of, and fully priced for, the megatrend? We think not, as most investors we meet are surprised by the structural uptrend in female participation, the on-going dynamics behind it, and the implications for consumer spending patterns. Understandably, the European clothes sector does trade at a valuation premium to the market (Chart I-10). But for many companies, the recent market hiccup has pulled down their valuation premiums to close to, or below, the long-term average from which the price has previously outperformed very strongly.

Chart I-10

The Valuation Premium On European Clothes Is Close To Its Long-Term Average

Fullscreen Fullscreen |  Interactive Chart Interactive Chart |

What Is In The Clothes Basket?

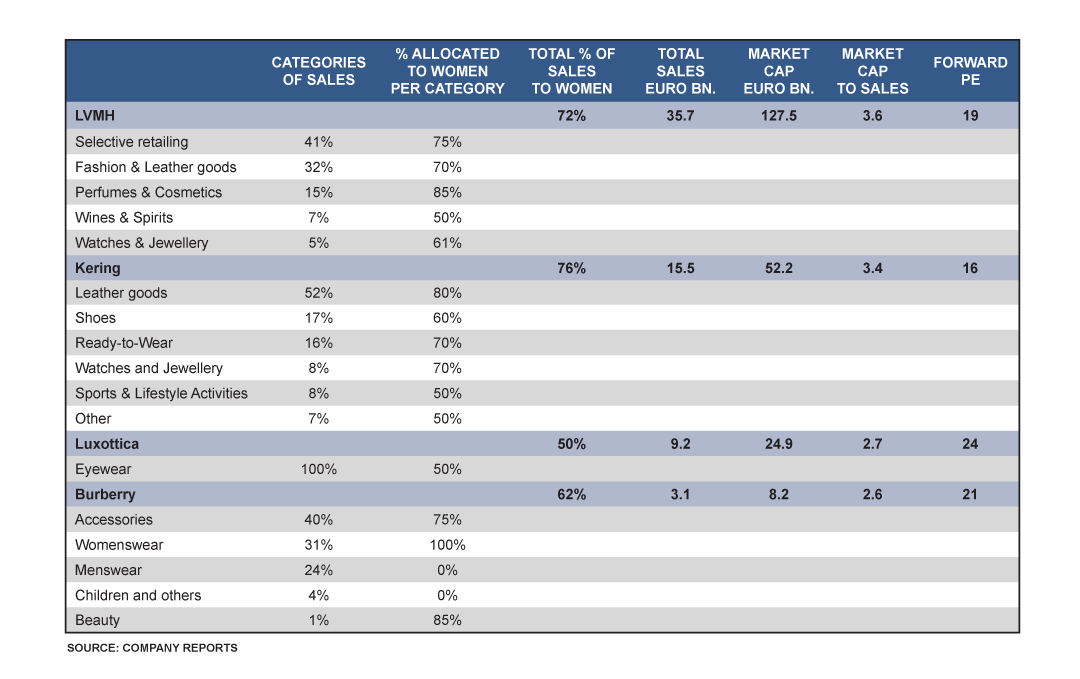

Pulling all of this together, the companies in our European clothes and accessories basket need to meet several criteria:

- A dominant or significant exposure to women’s clothes and/or accessories.

- A top-end brand (or brands) giving the company pricing power, and mitigating the very strong deflation in clothes prices. Avoid ‘fast fashion’.

- A reputation for sustainable development.

- A track-record of profit growth during the past decade.

- A forward price to earnings (PE) multiple of less than 25.

- A market capitalisation of at least €5 billion.

On the basis of these criteria, our European clothes and accessories basket contains four names: LVMH, Kering, Luxottica, and Burberry (Table I-5). Hermes meets most of the criteria but, trading on a forward PE close to 35 is very richly valued.

Table I-5

The European Clothes Basket

Fullscreen Fullscreen |

To be clear, this is not a short-term trade. Investors who buy the clothes basket outright need to have a multi-year investment horizon. Those investors who must also protect short-term performance should instead overweight the clothes basket relative to the broad market.

Dhaval Joshi, Senior Vice President

Chief European Investment Strategist

dhaval@bcaresearch.com

Footnotes

- 1 Please see the European Investment Strategy Special Report “Female Participation: Another Mega-Trend” published on April 6, 2017 and available at eis.bcaresearch.com

- 2 Please see the European Investment Strategy Special Report, “The Superstar Economy: Part 2”, January 19, 2017 available at eis.bcaresearch.com.

- 3 Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Expenditure Survey 2016 via SmartAsset, and Paymentsense.

You are reading a complimentary report. To find out more about our services,

You are reading a complimentary report. To find out more about our services,